The Subtle Art of Challenging a Brain

Have you ever had a flash of inspiration and checked to see if anyone else had ever thought of it? If you did an online search, chances are high that you'll find someone else who had the same idea. However, that doesn't change the fact that the idea was new to you! If you keep that in mind, you can appreciate the joys awaiting you inside every book you pick up, every video you watch and every song you hear.

Now, think about the last joke that made you laugh. The unexpected twist revealed a new pattern to your brain. Perhaps you had never thought about the scenario in the joke's context and the incongruity triggered you. (For more about this, check out Jerry Corley's explanation.)

While inspiration is a product of creative thinking, revelation is a done-for-you shortcut. As such, I believe that inspiration has a deeper, longer-term impact on our brains. (This may explain why we are able to describe our wacky ideas more clearly than we can recall all the elements of a funny joke.) In this context, I aim to create puzzle books that inspire readers.

Breaking the Mold

How in the world can I do that? Ironically, I borrow from the concept of comedy! Puzzles don't have to be a generic presentation of a stated problem to be solved. Though there's nothing wrong with that, I can spice up a word search just by using a witty title and a themed word list. That doesn't change the mechanics of the classic puzzle, but it may spark something in the solver's brain.

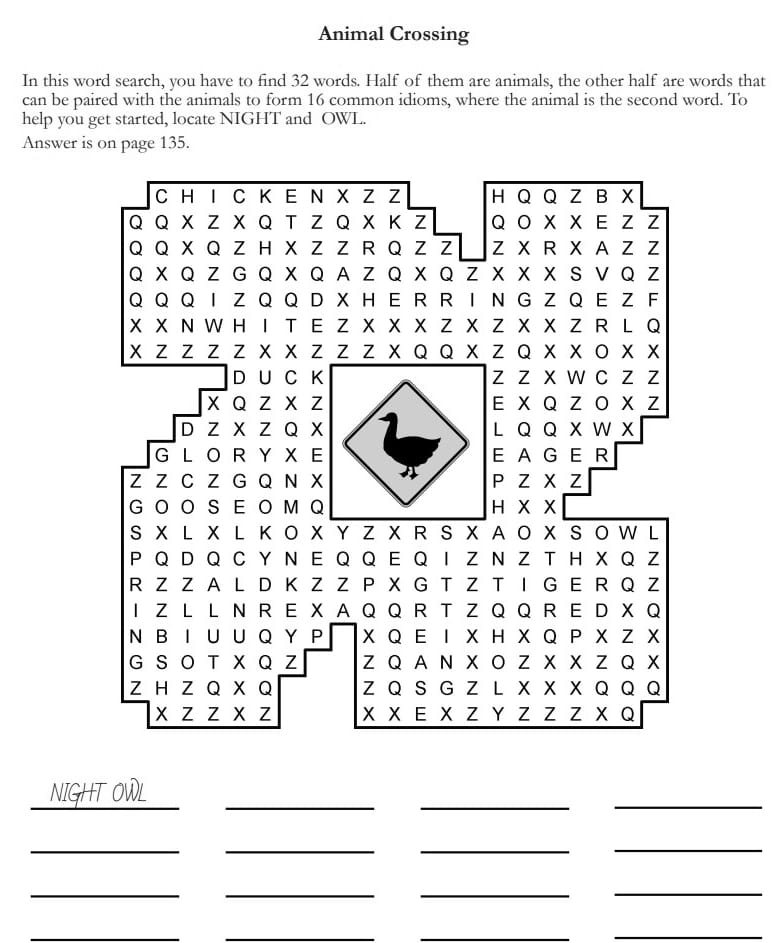

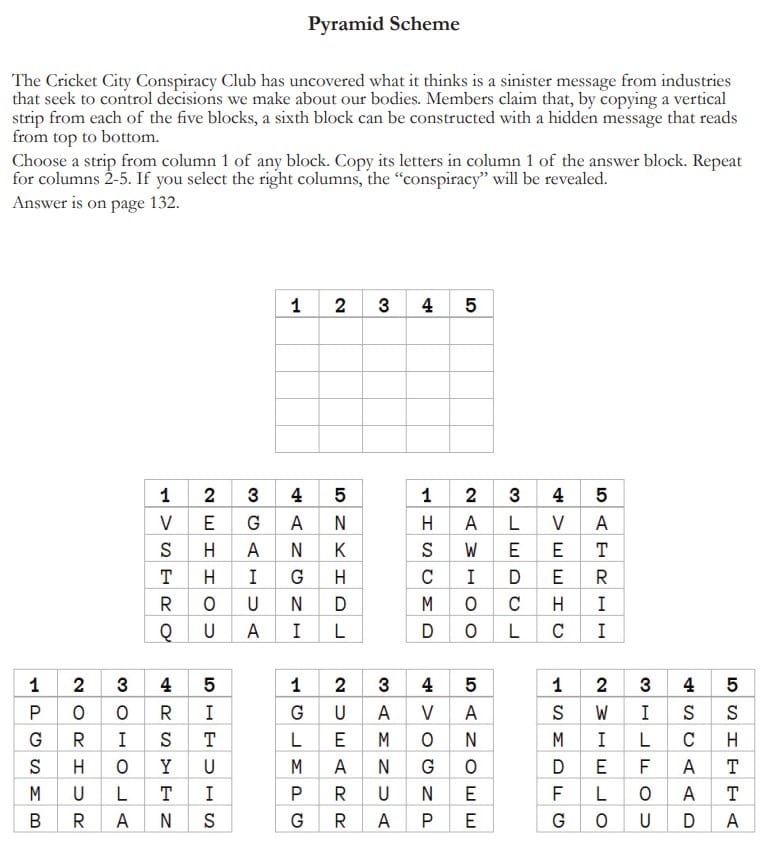

Continuing with word searches, the next step would be to change the mechanics for solving. Here's an example from my first book:

From the pun in the title to the stylized grid; from the reinforcing image to the instructions and lack of a word list, I've "broken the rules" of the classic word search. Now, the solver has to think of common idioms and verify them by locating the words!

I've used this rule-breaking idea in several other classic puzzles. However, to satisfy purists, the book also contains standard versions of those puzzles. The idea is to offer a little sump'n sump'n to change things up and challenge the reader to go down the rabbit-hole with me.

Comedy helps with other puzzles. This is why you'll often find humorous quips as the solution to cryptograms, Jumbles and other word puzzles. Finally, humor simply sets the tone for the entire book, reminding the reader to not take it too seriously. I do this by using whimsical scenarios, even in the puzzle's instructions.

Molding Something New

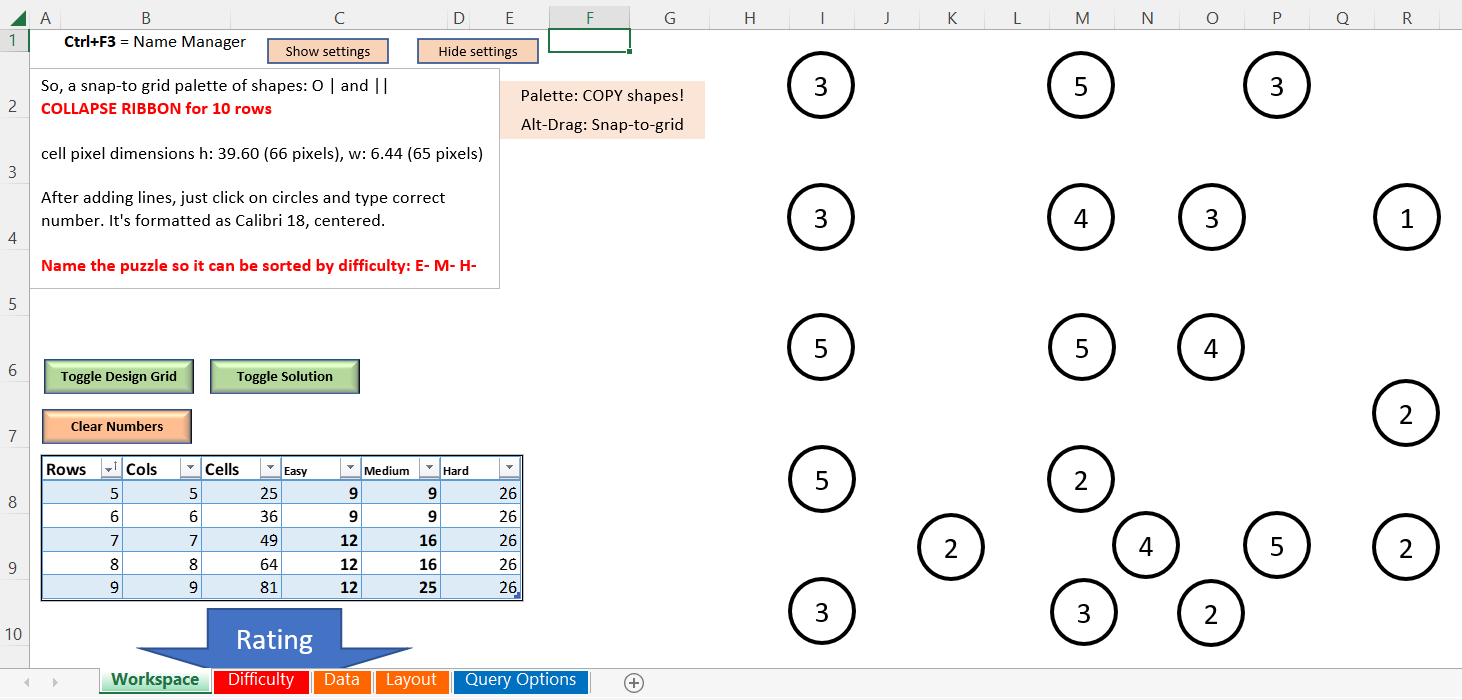

Another way to inspire readers is with unique puzzles. If you have no frame of reference for a particular puzzle construction, you must develop your own methods for solving. I'll give you one more example from my first book:

When I'm creating something weird like this, I try to offer up as many clues as possible. This is my subtle attempt to steer your brain in the right direction. How many clues do you see?

Pumping the Brakes

Don't be afraid to break a few rules to prod your audience from the passageway of predictability. But do be sure to triple-check each creation. When I created Pyramid Scheme, my design was based on a one-to-one mapping of column 1 to column 1, column 2 to column 2, etc. Then, I got bogged down trying to find suitable words. After an exhausting and exhaustive search, I found just the right words. However, I failed to notice that I had broken the one-to-one mapping!

I didn’t catch this until after I had published the book, so I had to create an updated set of instructions that, hopefully, clarifies that any chosen strip can go into any column in the answer. This may not matter to solvers, but it made me just a bit sad that I had to back away from the symmetry that I tried so hard to maintain.

The lesson here is to know when to fold ‘em. I have trashed a few puzzles that I had been working on, either because I couldn’t find solutions or because they were too arcane. Here’s one from the cutting floor:

That was a bit of stream-of-consciousness, wasn’t it? It’s a habit I formed when I used to journal on a site called 750words. These days, more of it stays in my head until it’s baked at least half-way.

Whether a puzzle is published or cut, I try to be “extra” during the production, and I find that it comes through on paper.